In all corners of the world there are challenging roads. Driver and vehicle are pushed to their limits by hairpin bends, ravines, potholes, sand, gravel, solitude and other risks. Six extreme examples reveal the adventures that await on the world’s most dangerous roads. Knorr-Bremse testing expert Elmar Müller explains below what kind of punishment brake systems have to withstand.

Yungas Road/Bolivia

Top of the list of the world’s most dangerous roads used to be Yungas Road in Bolivia, also known as Death Road, with an estimated 200 to 300 people killed in traffic accidents each year – until 2006, when an alternative, continuously asphalted stretch of the Ruta Nacional 3 was opened for the northern section of the highway. Yungas Road connects the capital La Paz in the highlands with Coroico in the north-eastern rainforest. From the La Cumbre Pass at 4,670 meters, the road now descends to 1,200 meters over a distance of 80 kilometers, crossing the principal climate zones of South America. The old route was 15 kilometers shorter, but it combined virtually every challenge that heavy truck drivers fear most: steep gravel roads without lighting, heavy rain and fog, landslides, oncoming traffic in sections where the road is less than four meters wide, rugged precipices without crash barriers – and driving on the left. It is standard to drive on the right in Bolivia, but drivers switch to the left on mountain roads with a high risk, because they are better placed to judge the road edge from the left of the vehicle. Since the Death Road has been largely left to thrill-seeking mountain bikers and tourists, the number of fatal traffic accidents has fallen drastically.

Karakorum Highway/China-Pakistan

If you’re looking for adventure, you’ll find it on the Karakorum (or Karakoram) Highway. Connecting western China with northwest Pakistan. It is known as a “Friendship Highway”, yet it is one of the world’s most dangerous roads. The border crossing stands at an altitude of 4,693 meters. The Khunjerab Pass marks the highest point of any asphalt highway in the world. On this section of the Silk Road, with its deep ravines and hairpin bends, the next thrill is always just around the corner, and the same goes for the splendid views of the surrounding seven- and eight-thousand-meter mountain peaks. These days the road is entirely asphalted on the Pakistani side as well, while the Chinese side has even been expanded to multiple lanes. The countries wanted to increase trade by making the mountain pass accessible all year round, even for heavy trucks. However, the matter is complicated by extreme weather. In winter, even in Tashkurgan in China, 120 kilometers away and more than 1,500 meters lower, temperatures sometimes drop to minus 30 to 40 degrees Celsius. According to official figures, there were almost 900 fatalities in accidents during the road’s construction up to its opening in 1978. Today almost a million motorists take the mountain route each year.

James Dalton Highway/Alaska

On the James Dalton Highway in Alaska, there is little point worrying about other road users. The road begins north of Fairbanks and ends 666 kilometers away in Deadhorse, near the oil fields of Prudhoe Bay on the coast of the Arctic Ocean. Its purpose is to transport supplies to the parallel Trans-Alaska Pipeline, oil workers and the few permanent residents of the area. At Milepost 115, the highway crosses into the Arctic Circle. Extreme winter temperatures down to minus 50 degrees Celsius, plenty of ice and other harsh weather conditions such as floods and snowstorms all leave their mark on the road. Even in August many potholes are left in the largely unpaved road surface. Most of all, the great solitude of the barren landscape makes this a harsh journey. Between Coldfoot and Deadhorse, there are no services for 384 kilometers. Should a vehicle break down on the icy road, it can only hope for assistance from one of the 250 or so trucks that use the Dalton Highway on an average day in the peak winter season. There is even less traffic in the summer. Cold and solitude make this highway one of the world’s most dangerous roads.

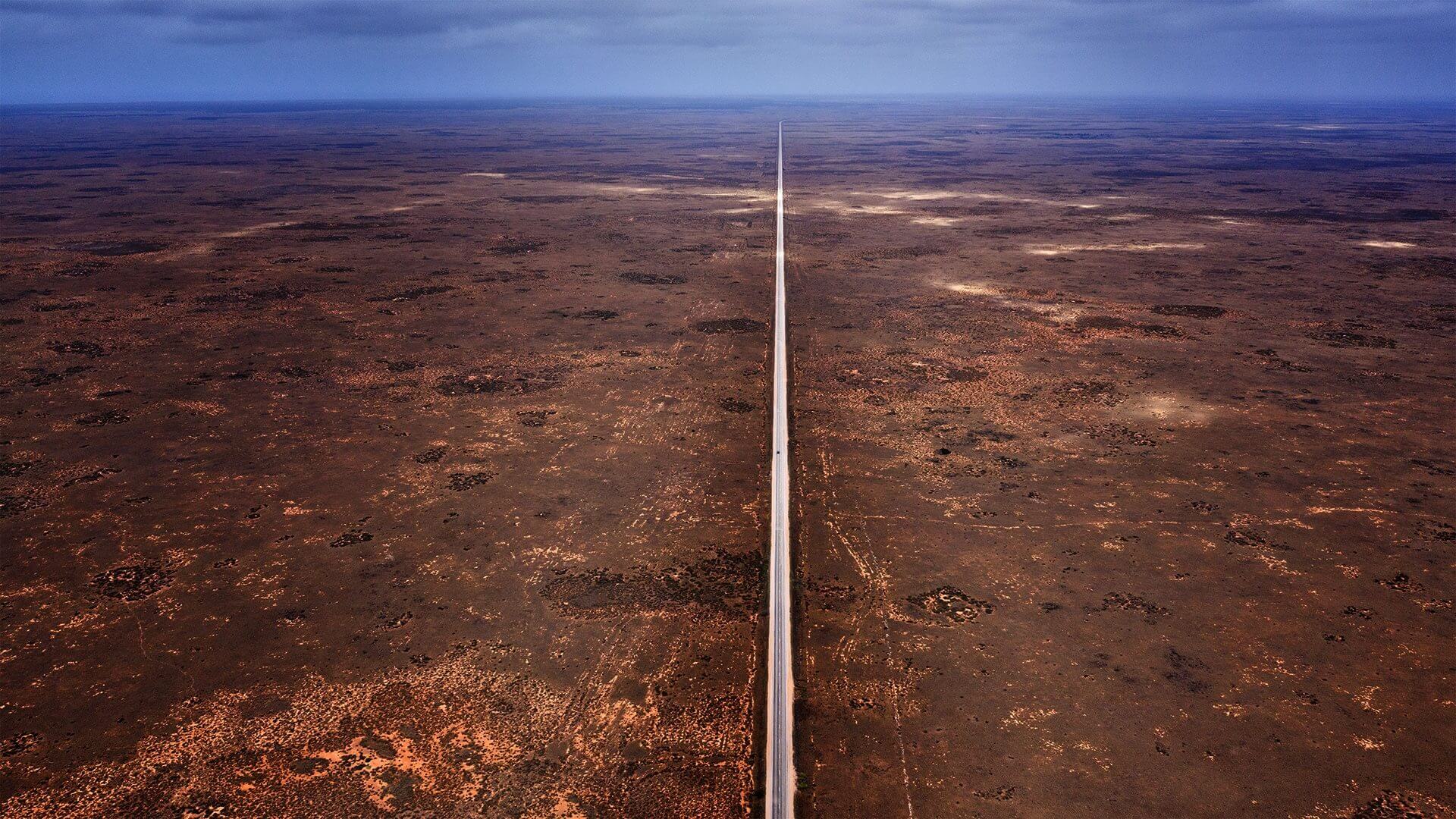

Eyre Highway/Australia

Australian heavy truck drivers are experts at dealing with solitude and monotony on the road. They get plenty of practice, especially on the Eyre Highway. Stretching for 1,675 kilometers between Port Augusta in the south and Norseman in the west, it holds the record for the world’s longest straight stretch of road. The section between Balladonia and Caiguna covers almost 150 kilometers without a single bend, curve or turn-off. And the rest of the Eyre Highway is not exactly a winding mountain road either. Even if accidents due to driver errors such as microsleep can be avoided, further dangers are lurking: kangaroos, emus and camels on the road regularly cause serious traffic accidents, especially in the evening and morning hours. What’s more, some sections of road can be used as landing strips for Australia’s Flying Doctors. So it’s important to be wary of aerial disturbances as well. Even in the Australian outback, an electronically controlled emergency braking system has calmed the nerves of many a driver.

N6/Algeria

The N6 runs north to south through Algeria for around 2,000 kilometers. The highway makes a gentle start in the port city of Oran on the Mediterranean. But after negotiating the 2,300-metre-high Atlas Mountains, with their passes, ravines and hairpin bends, it is easy to imagine the hostile combination of dust, heat and wind that follows. Between Reggane and the border to Mali, the road through the Tanezrouft region turns into an unmarked track. As a result, this route through the Sahara is hardly distinguishable from its desert surroundings. GPS navigation is strongly recommended here – as well as heating for the cool nights, air conditioning for daytime temperatures of up to 60 degrees Celsius, the obligatory spare tires and steady nerves. As far back as the Middle Ages, this route was used by the camel caravans of traveling merchants. Today it is one of the world’s most dangerous roads and a challenge for adventurous tourists and seasoned drivers.

MA-2141/Mallorca, Spain

A little masterpiece of road construction can be found on the north-west coast of the Balearic island Mallorca. The MA-2141 branches off the MA-10 towards the coastal village of Sa Calobra. This adventurous mountain road covers a difference in altitude of 680 meters over a distance of 13 kilometers. Italian engineer Antonio Paretti planned out its twelve hairpin bends. The road was completed in 1932 and has snaked its way through the rugged region ever since. The highlight of the road is known as the “necktie”, a 270-degree bend near Sa Moleta that almost circles back on itself. The reward for getting through the anxious moments – for instance, when local bus drivers or lowland tourists encounter oncoming traffic – are picture-perfect views of the ocean and a hidden bay between sheer cliffs that can otherwise only be reached by boat.

Braking on the world’s most dangerous roads

Dirt, cold, heat, vibrations – wheel brakes have to withstand extreme conditions and still perform reliably, even on the world’s most dangerous roads. Test rigs are used at Knorr-Bremse to simulate a whole variety of conditions. Elmar Müller, Manager Testing Department Air Disc Brake at Knorr-Bremse, explains how this works and why it is necessary.

What kind of conditions do brakes have to endure?

Our wheel brakes must be able to withstand all environmental and operating conditions on the roads. The spectrum ranges from dirt to stone chipping, moisture to corrosion, high and low temperatures to severe vibrations. As far as possible, we simulate all these influences under definable and replicable conditions in our test laboratory. To this end, we use climatic and corrosion chambers to expose our “test subjects” to severe temperature changes, for example, or aggressive substances. We use vibration test rigs that move our systems in all three dimensions to produce real loads, just as they occur on rough roads. We also use inertia dynamometers to push the brakes to their thermal performance limits. The work in the lab is complemented by field tests at Knorr-Bremse and at our customers’ premises, in which the prototypes are exposed to a variety of everyday operating conditions.

What are the critical factors?

Vibration is certainly one of the most critical and most spectacular factors. When driving over railway tracks, potholes or concrete joints, we have measured g-force acceleration of 25 to 30 g. For comparison, even the “worst” roller coasters produce g-forces of only 4 or 4.5 g. Any more would be life-threatening for riders of a roller coaster. When it comes to brakes, these forces are a source of stress. They particularly pose a challenge to movable parts like the pads, the complex wear adjuster and the caliper guidance system. Aside from vibration, corrosion and its influence on the smooth functioning of all brake components is a critical factor.

What about the red-hot brake discs?

The fact that the discs heat up to over 900 degrees Celsius after a steep downhill drive is not particularly dramatic in itself. However, at high temperatures, properties such as the friction coefficient and wear behavior of the brake pads change and the brake components expand noticeably. All this must be taken into account when designing and constructing the wheel brake and its components. If, in the worst case, the brake cools down as the vehicle remains stationary after a long downhill drive and the components therefore contract, naturally we have to ensure that the brake will still function properly. That’s why we also test precisely such cases, for example by parking the vehicle “hot” and fully loaded on an 18 percent incline, letting it cool down and then towing it away to determine the residual holding force.

Do iced-up discs reduce the braking force even more?

In a system that converts kinetic energy into heat and builds up clamping forces of over 20 tons, ice is not the main cause for concern. Very little ice will remain after the first brake application. At very low temperatures, however, certain effects come into play that can affect the agility of the brake. As lubricants become more viscous, the brake reacts more sluggishly, and this effect must not be allowed to overly restrict the braking dynamics in ABS control mode. However, our low-temperature tests in the laboratory and in Arjeplog, Sweden, show that we have this phenomenon well under control.

What do you see as the worst environmental conditions for a braking system?

What usually makes dramatic environmental conditions even more challenging is when they are combined with a tough operational profile. For example, in our field test applications we have milk collection trucks that place high demands on the brakes due to their operational profile, the heavy vehicle load and, of course, their difficult routes. Operating in multiple shifts, seven days a week, with very frequent brake applications, sometimes heavily loaded – all this can lead to continuously high operating temperatures of around 400 degrees Celsius, while driving on roads that may only be used for farm access. When all these factors come together, it can considerably reduce the lifetime of the friction pairing, so the vehicle service life is essentially running in fast-forward.